Back in the day, I discovered that creating digital art on the brand-new 128K Macintosh computer was exactly like drawing on an Etch-A-Sketch. In other words, I could do it and few others could.

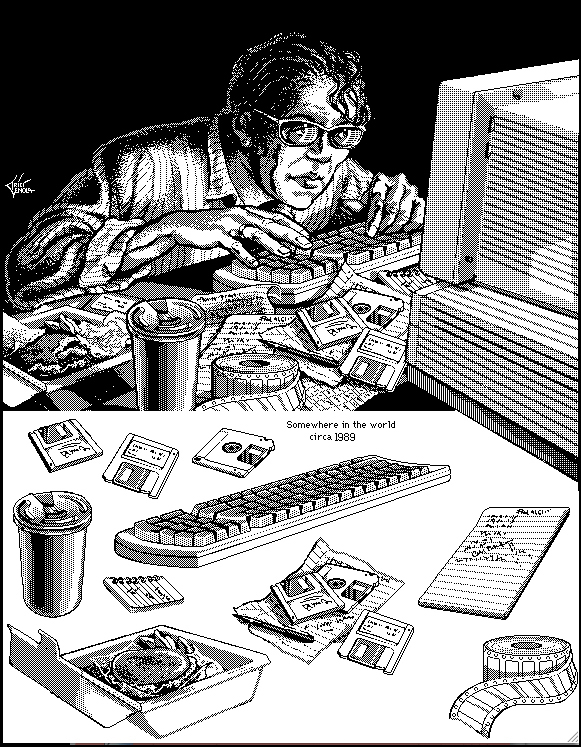

You drew with a mouse, you had black, you had white, you had a few tools. Bill Atkinson had given us MacPaint, and I used that. I didn’t know the difference between the software and the desktop. There were rudimentary scanners but I never used them. I thought the whole world knew how to draw directly onscreen using a mouse and MacPaint, so that’s what I did. Actually there were about four of us.

Because of this rare ability, I created several volumes of popular clip art, the first underground comic on the Mac, and got to speak at a lot of trade shows. This early black-and-white digital artwork was painstakingly created a pixel at a time, and must be used at 100 % or turn to mush.

The whole world was converting to computers. I was hired by studios to teach legendary artists how to create art on a computer. Get good and tired, I said, because your adult mind will forget that it can’t do what you’re asking it to do. By the end of the decade I was working all over the industry, including Disney, Paramount, BBDO (Apple’s ad agency at the time) and building digital game art for the likes of Super Mario Brothers and Barbie.

Brazen Images

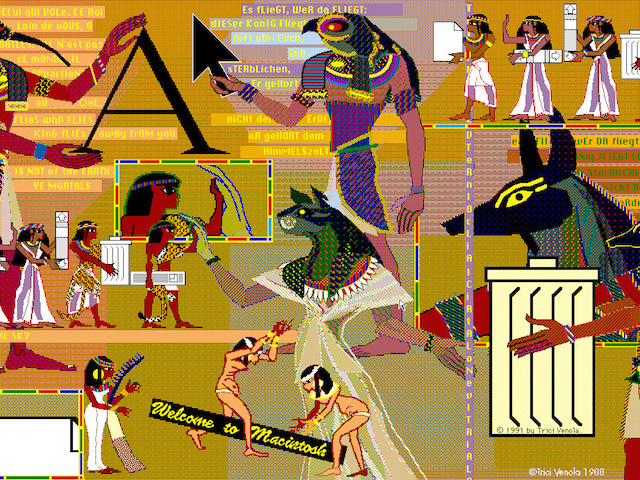

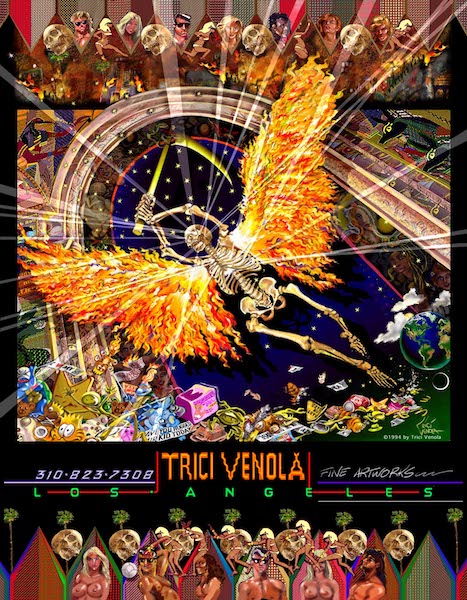

Brazen Images was a series begun on the first color Mac, in 1989-1990. The pieces were mouse-built using Studio 8, in 256 colors. It incorporated earlier work built in 8 colors in the color MacPaint. Two of the images, Little Egypt and A Chorus Line, were created in 8 colors only. It took so long to create each figure in each painting that I used them over and over in different combinations, like a vocabulary. It took me two months to build Dancing Fool, in Studio 8. Later I was able to work faster, and then in 1990 came Adobe Photoshop, with millions of colors, and the Wacom Tablet, a life-changer. I converted these early files to millions, with results like Earth Angel Flyer, but I kept these originals, and am I glad I did. They read like mosaics, and they took as long to build.

The Tiger in the Mac

When I started on the Mac in 1984 I didn’t understand the lingo enough to benefit from any of the manuals, so my knowledge is entirely empirical. I learned how to use the computer in a rage of frustrated ability. This rage was my driving force and it pushed me so hard that I found to my surprise that my work had made a name for itself. So I want to encourage you to concentrate on your art ability. I admire the computer as a means, rather than an end. My aim is entirely to create art.

There’s a belief afoot that the computer produces the art as it produces a straight line, that if my work isn’t happening, there’s some missing ingredient, some quick-fix magic combination of commands that will somehow make it all right. “Where is the tiger coming from?” asked a kid standing in the Miles booth at MacWorld back in 1985, watching me draw a running tiger from scratch on a FatMac. He said after ten minutes, “What program is that?”

I said, “MacPaint.”

“But where’s the tiger coming from?” he asked in genuine bewilderment, “isn’t there a program for drawing the tiger? That you just tell and it draws one?” and he wandered away leaving me wondering forever, Where does the tiger come from? From memory? From ability? Is it mine? Is it Bill Atkinson’s? He programmed MacPaint. How about Steve Jobs, who designed the Mac? How about all the people that built it? How about Eadward Muybridge, whose 1899 motion study of a tiger taught me how a tiger moved. Is he responsible for the tiger? Is it from all of us? Is an artist a synthesis of everything (s)he’s ever felt or seen, like they said back in school? Is this Beginning Theology 101? Is this course required? Hello?

It’s 1990, and I still don’t know where the darn tiger comes from. But I do know that there’s no program that will draw one from scratch, any size or pose or color or style, like I want it, without an artist at the helm. And there’s no magic answer for us artists except that we are each unique. We are the only variable. You can have identical setups: hardware; software; memory; working conditions: and the artists, left to themselves, will create totally different work. So don’t be intimidated by brilliant programmers, software publishers, technological wizards, and hardware junkies, and if they sneer at your lack of technological expertise, ask ‘em why they never bothered to learn to draw. We are none of us much without the others.

–Trici Venola, from Drawing the Lizard King, The Verbum Book of Bitmapped Illustration, August 1990 by Harcourt, Brace in connection with Verbum Magazine.